Polymer Words

Let’s start with the basic basics- definitions of a few key words you need to start your journey on the Path of Polymer Learning.

Polymer is the common name given to really big molecules. They’re also called “macromolecules,” which is just another way of saying big (macro) molecules. “Poly” comes from Greek and means many, and “mer” means units (not mer like in mermaid; sorry).

Monomer also comes from Greek and means “one” unit. Monomers are used to make polymers. They also exist in their right and can be used to make lots of other bigger molecules that aren’t polymers.

Oligomer is a really small polymer made of just a few or few dozen monomer units. Some oligomers are useful in natural products chemistry, for example. Hence the “isoprene rule” which applies to hydrocarbons and is based on units consisting of 5 carbon segments known as the monomer “isoprene.”

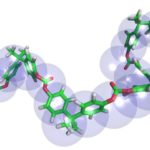

Polymer chain refers usually to the entire polymer molecule although sometimes to just the backbone. A chain consists of many monomers linked together through covalent bonds.

Polymer backbone indicates what atoms make up the main chemical bonds forming the polymer. For example, the monomer ethylene (CH2=CH2) forms polyethylene which has thousands of ethylene monomers all linked together in one huge chain. The backbone consists of just carbon atoms linked together, with each carbon atom also connected to two hydrogen atoms for a total of 4 bonds per carbon (a general rule in organic chemistry). Polymer backbones are more complicated for most other polymers.

Pendent group is a way of referring to some group of atoms that are not part of the backbone but are chemically bonded to an atom of the backbone. The simplest pendent group would be a hydrogen atom of polyethylene. In polypropylene, the backbone is the same as in polyethylene but on every other carbon there’s attached a pendent CH3 group.

Functional group is a generic organic chemistry term for some group of atoms joined together through chemical bonds. Usually, a functional group has more than just carbons and hydrogens in it and it is “reactive” in some way. Technically, however, the CH3 pendent group of polypropylene is a functional group although not really very reactive. So much for convention.

Molecular weight is a term used throughout chemistry. It refers to the “weight” of a molecule (who’d have guessed). Atoms have a specific atomic weight that depends on the number of protons, neutrons and electrons the atom has. These weights are given in “atomic mass units.” Here’s the simple way to think about this: one hydrogen atom has a weight or mass of one atomic mass unit. All other atoms and molecules are expressed in multiples of that, more or less.

Polymer molecular weight is much more complicated than the molecular weight of a small molecule like water. All molecules of good old H2O, for example, have the same molecular weight of 18 amu (mostly, anyway; a few have isotopes which make their weights a little different. We’ll discuss that more later). Thus, chemists say that all water molecules are the same and have the same molecular weight. Not true for polymers. Because of the way they’re made, any given batch of polymer molecules will have some chains longer than others. There’s a distribution of chain lengths and therefore molecular weights for all the chains in the mix. More about this later when we talk about how to measure molecular weights of polymers.

An end group is what we call whatever atom or functional group is at each end of a linear polymer chain. There are reasons for specifically naming this part of a polymer that will be clear when we talk about intermolecular interactions later.

Initiator is the name for a special kind of reactive molecule that, well, initiates something. The context for the chemical process involved in polymer synthesis is usually a chain reaction. One initiator can lead to a series of sequential reactions that all involve the same intermediate and same product over and over again: one initiator, lots of product molecules. And because all or part of an initiator molecular ends up at the end of any given polymer chain made this way, it is the end group.

Free radical polymerization is one example of a chain reaction involving an initiator. The chemistry is complicated and we won’t go into it just yet. Examples of polymers made this way are some kinds of polyethylene (yes, there are different kinds), polystyrene and poly(vinyl chloride). So it’s getting interesting now, yes?

A catalyst is different than an initiator, although many people confuse the two. In organic chemistry, a catalyst is a chemical agent that makes a reaction easier, faster or more likely to happen in one particular way: it catalyzes the reaction. Unlike an initiator, a catalyst is NOT used up during the reaction (usually, although sometimes unwanted side-reactions will kill a catalyst). An initiator is always used up to start the reaction by forming a chemical bond to whatever it reacts with. A catalyst doesn’t. An example of a catalyst would be a transition metal (remember what that is from general chem?) used to make very high molecular weight and high density polyethylene which is different from the lower molecular weight and branched polyethylene made by radical initiation. Now it’s getting more interesting!

That’s enough definitions to get us started on the real “meat” of this course. We’ll have more later scattered throughout the text. I’ll put those all together in a glossary you can find at the end of the lessons. But for now, let’s take a quiz! Click on the definitions quiz and see how you do. Remember the old saying, “try, try again,” and apply it to the quizzes. Going through the questions more than once helps you learn the material better.

So now, on to what a polymer chain or macromolecule is like, what examples help you understand some of the concepts related to the words defined above: Polymer Analogies